Everything That Didn't Fit

Announcing my new solo show at bitforms gallery, up from Feb 3 - March 5, 2022

Today I’m getting straight to the point: I've got a solo show opening in less than a week!

The show is called Everything That Didn't Fit. It's about those things — experiences, histories, scents, memories, data, reports, and more — that are missing from technocolonial systems of collection. We collect things we value, and the show is about what doesn't fit that. But it also lays out a kind of response through community ritual that undoes and expands the assumptions that determine what matters in the first place.

It's not my first solo show, but I’m extra excited because it's a mix of old and new work and it’s the first solo show I've had in the city I’ve been trying to leave lived in for a decade. The opening reception is Feb 3, 6-8pm at bitforms gallery in the LES, and everyone's invited. Between the cold (disappointed to report that it's snowing as I write this) and Omicron, this is a strange time to have a show, but I feel lucky. I like the interplay between legibility and ambiguity that artmaking allows, and I'm excited to show some of the works that have emerged from that back-and-forth.

Anyway, the official exhibition press release is here with a longer explanation and previews of the work. But for this month's newsletter, I want to give a behind-the-scenes peek at what I've been thinking of while hustling to finish everything for the show. I've written in other places about missing things and the structural reasons why not everything we collect gets to count as proof. But I haven't written as much about the other aim that the show has, which is to push for a way to challenge, expand, and undo the categories that inform Western society (and which have been exported out to the rest of the world.)

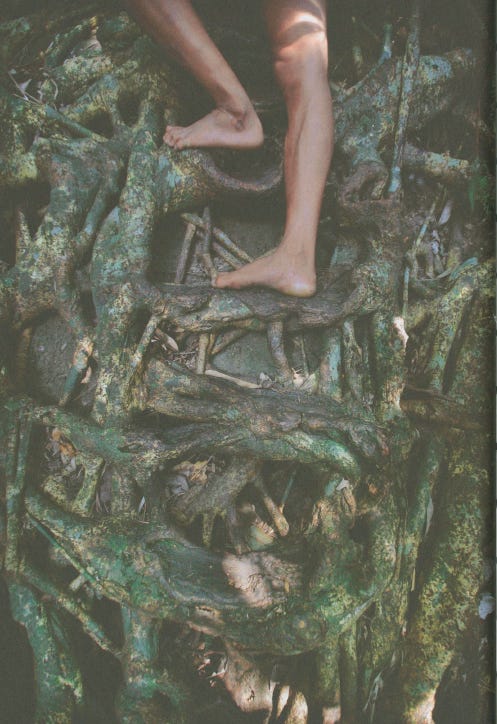

The explanation starts with this image, though you'll have to stick with me to understand why:

The above image is a bridge made of living tree roots, created and managed by the Khasi indigenous hill tribe of Northern India1. There are many more in the region like this one. Each one is constructed by Khasi builders who guide the growth of the roots of rubber fig trees. One bridge takes thirty years to come into its own, so any new bridge is planned a decade in advance and its creation spans an entire generation.

For us non-Khasi folks, the living root bridges are wild! They feel magical. It's so awe-inspiring to see those thick roots intertwined with each other, forming new structures. But the tree root bridges are actually a technical solution developed over centuries to solve a recurring problem. The Khasi people live in villages, and as Julia Davis writes in LO-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism,

“During the monsoon, travel between villages is cut off by floodwaters that transform the landscape from a thick canopy to isolated forest islands. The Khasi have developed the only bridges able to withstand the force of the monsoonal rains....these constructions are living bridges and ladders, created by guiding growing trees across the riverine corridors of the Jaintis Hills region.”2

Unlike mechanical ones, systems made of living things only get stronger and more complex over time. This is what makes the tree root bridges perfect solutions to the problem of withstanding monsoon rains and allowing for travel through inaccessible spaces. But they only work (tbh they only exist) because they're not a solely technological solution.

The Khasi's bridges are completely engrained in various parts of their culture, spirituality, and cosmology. For instance: Khasi folklore demarcates a certain elevation along the riverbank as sacred, and in that area there's a taboo associated with plucking and cutting leaves. This taboo doesn't just serve the needs of folklore; it protects the growth of living root bridges (and their sibling structure, root ladders) by making it forbidden to disturb those areas. And as Khasi architect Prabhat D Sawyan says, "There is hardly a waterfall, cave, stonehenge, or rock formation around which no legend or lore exists, and these natural assets dominate the living psyche and cultural modes of the people....it's no wonder that the language and culture of the Khasi people emanates from this rain-swept principality."3

Now, finally, here's why I've jumped from talking about my little solo show this February in NYC to the age-old Khasi practice of guiding root bridges in Northern India: the Khasi root bridges and ladders are just one example of the fact that technological systems only emerge out of the values and assumptions of a society, even as they then go on to shape those values and assumptions. These values and assumptions are what create the conditions for technological solutions. You can't have living tree root bridges and ladders unless you already think of trees as partners rather than raw resource; unless you value moving slowly and passing down local knowledge over time; unless you are willing to forsake expediency for robustness and sustainability; unless you are more concerned with valuing interconnectedness than profit; unless your history, cosmology and lifestyle supports the importance of living tree bridges.

In Everything That Didn't Fit, I'm lightly pointing at what has created the conditions for the digital (and cultural, and natural, and cosmological) systems that we have now. And of course, just like the technology of tree bridges, our technological systems are tied to our collective history, our society's mainstream values, our views of the natural world, modernity's Western colonial overarching influence, the prevalence of racial capitalism, and so much more.

As much as I'm gesturing at those conditions, I'm hinting at what would take to change them. But that's a question that is much bigger than one show, and far too pressing to just be the focus of one art practice. Good thing none of us do this work alone....!

If you have thoughts on this, reach out to me. Or even better, if you're in NYC, come to the opening! You can find details about it and Covid safety at the event here.

//////

One last note: Finally I can announce that I'm a 2022 Creative Capital grantee! The project I received funding for is intense in the best way, one of those times when I feel like I'm not just commenting on conditions but actively intervening and holding multiple spaces at the same time. It’s tied to this exhibition but wholly different in approach. More on that coming soon, but here’s a sneak peek.

Tree roots are the original information cables, you can’t change my mind.

This quote taken from Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism, which is written by Julia Davis.

Another quote from Julia Davis’ Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism. This book is so good, I really recommend it. The Khasi’s bridges are just one example of many more mind-opening approaches to technology that are interwoven with the natural world. It’s a different way of approaching technology, and a deeply needed one.